This step is present only when the trading client is an institution. Every institution engages the services of an agency called a custodian to assist them in clearing and settlement activities. The figure below illustrates this.

As the name suggests, a custodian works in the interest of the institution that has engaged its services. Institutions specialize in taking positions and holding. To outsource the activity of getting their trades settled and to protect themselves and their shareholder’s interests, they hire a local custodian in the country where they trade. When they trade in multiple countries, they also have a global custodian who ensures that settlements are taking place seamlessly in local markets using local custodians.

As the name suggests, a custodian works in the interest of the institution that has engaged its services. Institutions specialize in taking positions and holding. To outsource the activity of getting their trades settled and to protect themselves and their shareholder’s interests, they hire a local custodian in the country where they trade. When they trade in multiple countries, they also have a global custodian who ensures that settlements are taking place seamlessly in local markets using local custodians.As discussed earlier, while giving the orders for the purchase/sale of a particular security, the fund manager may just be in a hurry to build a position. He may be managing multiple funds or portfolios. At the time of giving the orders, the fund managers may not really have a fund in mind in which to allocate the shares. To avoid a market turning unfavorable, the fund manager will usually give a large order with the intention of splitting the position into multiple funds. This is to ensure that when he makes profits in a large position, it gets divided into multiple funds, and many funds benefit.

The broker accepts this order for execution. On successful execution, the broker sends the trade confirmations to the institution. The fund manager at the institution during the day makes up his mind about how many shares have to be allocated to which fund and by evening sends the broker these details. These details are also called allocation details in market parlance. Brokers then prepare the contract notes in the names of the funds in which the fund manager has requested allocation.

Along with the broker, the institution also has to liaise with the custodian for the orders it has given to the broker. The institution provides allocation details to the custodian as well. It also provides the name of the securities, the price range, and the quantity of shares ordered. This prepares the custodian, who is updated about the information expected to be received from the broker. The custodian also knows the commission structure the broker is expected to charge the institution and the other fees and statutory levies.

Using the allocation details, the broker prepares the contract note and sends it to the custodian and institution. In many countries, communications between broker, custodian, and institutions are now part of an STP process. I’ll talk about STP in another post. This enables the contract to be generated electronically and be sent through the STP network. In countries where STP is still not in place, all this communication is manual through hand delivery, phone, or fax.

On receipt of the trade details, the custodian sends an affirmation to the broker indicating that the trades have been received and are being reviewed. From here onward, the custodian initiates a trade reconciliation process where the custodian examines individual trades that arrive from the broker and the resultant position that gets built for the client. Trades are validated to check the following:

- The trade happened on the desired security.

- The trade is on the correct side (that is, it is actually buy and not sell when buy was specified).

- The price at which the trade happened is within the price range specified by the institution.

- Brokerage and other fees levied are as per the agreement with the institution and are correct.

The custodian usually runs a software back-office system to do this checking. Once the trade details match, the custodian sends a confirmation to the broker and to the clearing corporation that the trade executed is fine and acceptable. A copy of the confirmation also goes to the institutional client. On generation of this confirmation, obligation of getting the trade settled shifts to the custodian (a custodian is also a clearing member of the clearing corporation).

In case the trade details do not match, the custodian rejects the trade, and the trades shift to the broker’s books. It is then the broker’s decision whether to keep the trade (and face the associated price risk) or square it at the prevailing market prices. The overall risk that the custodian is bearing by accepting the trade is constantly measured against the collateral that the institution submits to the custodian for providing this service.

Clearing and Settlement

With hundreds of thousands of trades being executed every day and thousands of members getting involved in the entire trading process, clearing and settling these trades seamlessly becomes a humungous task. The beauty of this entire trading and settlement process is that it has been taking place on a daily basis without a glitch happening at any major clearing corporation for decades.

After the trades are executed on the exchange, the exchange passes the trade details to the clearing corporation for initiating settlement. Clearing is the activity of determining the answers to who owes the following:

- What?

- To whom?

- When?

- Where?

The entire process of clearing is directed toward answering these questions unambiguously. Getting these questions answered and moving assets in response to these findings to settle obligations toward each other is known as settlement. This is illustrates with the figure below.

Thus, clearing is the process of determining obligations, after which the obligations are discharged by settlement. It provides a clean slate for members to start a new day and transact with each other.

When members trade with each other, they generate obligations toward each other. These obligations are in the form of the following:

- Funds (for all buy transactions done and that are not squared by existing sale positions)

- Securities (for all sale transactions done)

Normally, in a T+2 environment, members are expected to settle their transactions after two days of executing them. The terms T+2, T+3, and so on, are the standard market nomenclature used to indicate the number of days after which the transactions will get settled after being executed. A trade done on Monday, for example, has to be settled on Wednesday in a T+2 environment.

As a first step toward settlement, the clearing corporation tries to answer the “what?” portion of the clearing problem. It calculates and informs the members of what their obligations are on the funds side (cash) and on the securities side. These obligations are net obligations with respect to the clearing corporation. Since the clearing corporation identifies only the members, the obligations of all the customers of the members are netted across each other, and the final obligation is at the member level. This means if a member sold 5,000 shares of Microsoft for client A and purchased 1,000 shares for client B, the member’s net obligation will be 4,000 shares to be delivered to the clearing corporation. Because most clearing corporations provide novation (splitting of trades), these obligations are broken into obligations from members toward the clearing corporation and from the clearing corporation toward the members. The clearing corporation communicates obligations though it’s clearing system that members can access. The member will normally reconcile these figures using data available from its own back-office system. This reconciliation is necessary so that both the broker and the clearing corporation are in agreement with what is to be exchanged and when.

In an exchange-traded scenario, answers to “whom?” and “where?” are normally known to all and are a given. “Whom?” in all such settlement obligations is the clearing corporation itself. Of course, the clearing corporation also has to work out its own obligations toward the members. Clearing members are expected to open clearing accounts with certain banks specified by the clearing corporation as clearing banks. They are also expected to open clearing accounts with the depository. They are expected to keep a ready balance for their fund obligations in the bank account and similarly maintain stock balances in their clearing demat account. In the questions on clearing, the answer to “where?” is the funds settlement account and the securities settlement account.

The answers to “what?” and “when?” can change dramatically. The answer to “when?” is provided by the pay-in and pay-out dates. Since the clearing corporation takes responsibility for settling all transactions, it first takes all that is due to it from the market (members) and then distributes what it owes to the members. Note that the clearing corporation just acts as a conduit and agent for settling transactions and does not have a position of its own. This means all it gets must normally match all it has to distribute.

Two dates play an important role of determining when the obligation needs to be settled. These are called the pay-in date and the pay-out date. Once the clearing corporation informs all members of their obligations, it is the responsibility of the clearing members to ensure that they make available their obligations (shares and money) in the clearing corporation’s account on the date of pay-in, before the pay-in time. At a designated time, the clearing corporation debits the funds and securities account of the member in order to discharge an obligation toward the clearing corporation. The clearing corporation takes some time in processing the pay-in it has received and then delivers the obligation it has toward clearing members at a designated time on the date of pay-out. It is generally desired that there should be minimal gap between pay-in and pay-out to avoid risk to the market. Earlier this difference used to be as large as three days in some markets. With advancement in technology, the processing time has come down, and now it normally takes a few hours from pay-in to pay-out. Less time means less risk and more effective fund allocation by members and investors. The answer to “when?” is satisfied by the pay-in and pay-out calendar of the clearing corporation, which in turn is calculated depending upon the settlement cycle (T+1, T+2, or T+3).

Answers to “what?” depend on the transactions of each member and their final positions with respect to the exchange. Suppose a member has done a net of buy transactions; he will owe money to the clearing corporation in contrast to members who have done net sell transactions, who will owe securities to the clearing corporation. To effect settlements, the clearing corporation hooks up with banks (which it normally calls clearing banks) and depositories. It has a clearing account with the clearing bank and a clearing account with the depository as well. A clearing bank account is used to settle cash obligations, and a clearing account with a depository is used to settle securities obligations.

That is a very long post on the last two steps of the life cycle of a trade. Have a nice weekend my readers and have a happy new year.

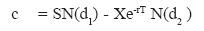

where: N(d) is the value of the Normal distribution function at the point d; d = d1 or d2. The other symbols are defined as follows:

where: N(d) is the value of the Normal distribution function at the point d; d = d1 or d2. The other symbols are defined as follows: You will notice in this formula that the price does not depend upon the mean μ. In everyday language, investor expectations are irrelevant to the price of the option. This may seem like a startling statement. However, it is simply a reflection of the fact that investor expectations do play a role, but only in the price of the underlying physical. The option itself is purely a play on the physical, and the effects of changing expectations can be hedged away by means of the corresponding effect on the physical (the latter being the hedge).

You will notice in this formula that the price does not depend upon the mean μ. In everyday language, investor expectations are irrelevant to the price of the option. This may seem like a startling statement. However, it is simply a reflection of the fact that investor expectations do play a role, but only in the price of the underlying physical. The option itself is purely a play on the physical, and the effects of changing expectations can be hedged away by means of the corresponding effect on the physical (the latter being the hedge).